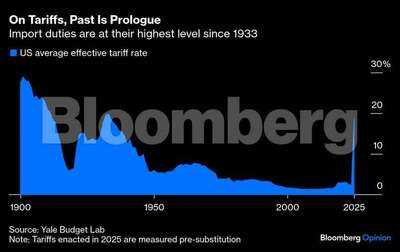

Amid the president’s blitz of tariff initiatives, the April “Liberation Day” scheme is an outlier. Rather than targeting specific products or countries to advance a policy goal, it imposed across-the-board duties, relied on vague justifications, and proved so harsh and omnidirectional that it induced a market crash. It was also premised on an arcane emergency-powers law — which may soon prove its undoing.

In announcing the tariffs, the White House asserted that persistent US trade deficits in goods amounted to “an unusual and extraordinary threat” and cited the International Emergency Economic Powers Act to impose a 10% baseline import duty, along with country-specific “reciprocal” rates ostensibly derived from trade balances.

Its reasoning was puzzling. Decades of persistent deficits with dozens of countries would hardly qualify as unusual or extraordinary. IEEPA was intended to address overseas crises — through measures such as sanctions or asset freezes — not to regulate run-of-the-mill trade policy. And Congress has specified in detail how presidents may wield tariff powers, including through Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act and Sections 122 and 301 of the Trade Act.

So why did the White House rely on IEEPA instead of these well-established authorities? The most likely reason is that (in theory) it enables the president to act unilaterally. Other tariff statutes can entail lengthy administrative processes and are subject to various limitations imposed by Congress. IEEPA, by contrast, could allow for a maximal assertion of executive power with minimal red tape.

No president has ever wielded IEEPA in this way, however, and for good reason: The word “tariff” appears nowhere in the statute’s text. It was thus foreseeable, even on Liberation Day, that these measures would be subject to potentially fatal legal challenges. The White House went ahead anyway and now finds itself in a bind.

On Aug. 29, the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit upheld a ruling by the Court of International Trade that the administration had acted unlawfully. Last week, the Supreme Court agreed to expedite its review of the case, with a hearing likely for November. If the top court rules that the tariffs are invalid, the government may need to rescind them — a possibility the president has described as “a total disaster.”

The IEEPA tariffs are indeed significant, affecting trillions of dollars in trade. They’ve made up 61% of total assessed import duties since January and now average about $500 million a day. If they need to be refunded, according to Bloomberg Economics, the bill could exceed $130 billion by year-end. The administration claims (perhaps self-interestedly) that a delayed ruling might apply to $1 trillion in revenue, implying a much larger unexpected expense.

Although striking down the tariffs might benefit companies, it wouldn’t be an unalloyed victory. Quite how they’d seek redress isn’t clear. (US Customs and Border Protection had to write an entirely novel rulebook to administer a previous round of relief.) The administration may yet impose replacement measures under other laws. In the meantime, automakers, apparel manufacturers, pharma companies and other businesses will need to make investment decisions with little idea of what rules they’ll end up facing.

It bears repeating that these tariffs would’ve been a bad idea even if they had been undertaken with care and propriety. They’re taxing Americans to the tune of $1,200 or so a year. They’ve needlessly slowed growth, boosted the cost of essential inputs, contributed to rising consumer prices and invited painful retaliation, all while imposing a punishing administrative burden on businesses. The US and the world are poorer for them.

Simply placing these tariffs on sounder legal footing won’t undo the damage that’s already been done. Far better for the White House to let them expire, blame the courts, and then reap the benefits of unfettered trade and improved growth.

This view is of the Bloomberg Editorial Board

In announcing the tariffs, the White House asserted that persistent US trade deficits in goods amounted to “an unusual and extraordinary threat” and cited the International Emergency Economic Powers Act to impose a 10% baseline import duty, along with country-specific “reciprocal” rates ostensibly derived from trade balances.

Its reasoning was puzzling. Decades of persistent deficits with dozens of countries would hardly qualify as unusual or extraordinary. IEEPA was intended to address overseas crises — through measures such as sanctions or asset freezes — not to regulate run-of-the-mill trade policy. And Congress has specified in detail how presidents may wield tariff powers, including through Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act and Sections 122 and 301 of the Trade Act.

So why did the White House rely on IEEPA instead of these well-established authorities? The most likely reason is that (in theory) it enables the president to act unilaterally. Other tariff statutes can entail lengthy administrative processes and are subject to various limitations imposed by Congress. IEEPA, by contrast, could allow for a maximal assertion of executive power with minimal red tape.

No president has ever wielded IEEPA in this way, however, and for good reason: The word “tariff” appears nowhere in the statute’s text. It was thus foreseeable, even on Liberation Day, that these measures would be subject to potentially fatal legal challenges. The White House went ahead anyway and now finds itself in a bind.

On Aug. 29, the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit upheld a ruling by the Court of International Trade that the administration had acted unlawfully. Last week, the Supreme Court agreed to expedite its review of the case, with a hearing likely for November. If the top court rules that the tariffs are invalid, the government may need to rescind them — a possibility the president has described as “a total disaster.”

The IEEPA tariffs are indeed significant, affecting trillions of dollars in trade. They’ve made up 61% of total assessed import duties since January and now average about $500 million a day. If they need to be refunded, according to Bloomberg Economics, the bill could exceed $130 billion by year-end. The administration claims (perhaps self-interestedly) that a delayed ruling might apply to $1 trillion in revenue, implying a much larger unexpected expense.

Although striking down the tariffs might benefit companies, it wouldn’t be an unalloyed victory. Quite how they’d seek redress isn’t clear. (US Customs and Border Protection had to write an entirely novel rulebook to administer a previous round of relief.) The administration may yet impose replacement measures under other laws. In the meantime, automakers, apparel manufacturers, pharma companies and other businesses will need to make investment decisions with little idea of what rules they’ll end up facing.

It bears repeating that these tariffs would’ve been a bad idea even if they had been undertaken with care and propriety. They’re taxing Americans to the tune of $1,200 or so a year. They’ve needlessly slowed growth, boosted the cost of essential inputs, contributed to rising consumer prices and invited painful retaliation, all while imposing a punishing administrative burden on businesses. The US and the world are poorer for them.

Simply placing these tariffs on sounder legal footing won’t undo the damage that’s already been done. Far better for the White House to let them expire, blame the courts, and then reap the benefits of unfettered trade and improved growth.

This view is of the Bloomberg Editorial Board

You may also like

'This Is What Charlie Wanted': Erika Kirk named CEO and board chair of Turning Point USA; will succeed late husband

'Don't call us suicidal!' terminally ill assisted dying campaigners tell peers

Strictly Come Dancing's Tess Daly's clever trick to 'work out winner' as show returns

9,909 in, ONE out - Keir Starmer's migrant farce laid bare as 2 key problems remain

Craig Revel Horwood calls for ex Strictly pro's return almost 10 years on from sudden exit