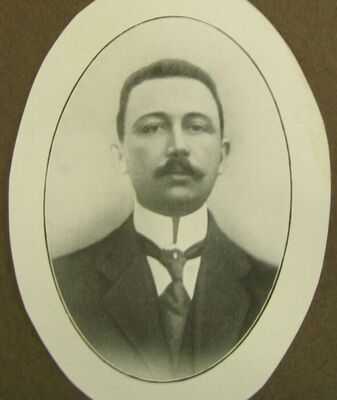

The last words by Dieudonné Lambrecht in a final letter to his wife and family on April 17, 1916, from a prison cell in Belgium were impossibly moving: "In heaven, I will watch over you... Think of my life as having been given up for my country - it will make my death seem less painful to you... I am only doing what so many have done before me and will do again." The following day he was shot by the Germans for spying for the British secret service. No amount of torture during his long interrogations could break him and he gave up not a single name of his agents.

He ended his last letter: "For our darling little daughter, for my parents and for you, receive on this letter, the last affectionate kisses of he, who was. Your Donné." More than 20 years after I first read these words, they still have the power to move me to tears. Today, the desolate, God-forsaken fortress of Chartreuse in Liège is derelict but it was the scene of many deaths by firing squad of courageous Belgians who helped the Allies.

The Germans lost no time in placing posters about Lambrecht's death on the walls of public buildings to discourage others from espionage. But instead of deterring Lambrecht's agents, who were lying low across Belgium, his execution served as a catalyst for defiance. In death, he became a powerful figure. Like a phoenix rising from the ashes, the remnants of his espionage service emerged as one of the greatest spy organisations of the First World War.

German forces had invaded Belgium in August 1914 and occupied the country. The British Expeditionary Force had landed in France and headed for Belgium to repel any advance but they were no match for the million-strong German forces. For the next four years, both sides engaged in bloody battles and trench warfare along a frontline of hundreds of miles that resulted in millions of casualties and deaths of young men.

Back in London, British intelligence desperately needed to see behind the German lines to understand enemy troop movements, weaponry and any preparations for an offensive and then pass this to British army headquarters (GHQ) in France. The eyes and ears on the ground were ordinary Belgian men and women - prepared to risk their lives as agents, couriers, run safehouses and letterboxes. They worked for a network that came to be known as the White Lady, or La Dame Blanche.

It was under the leadership of Lambrecht's cousin, Walthère Dewé, who had taken up the mantle after Lambrecht's execution. The clandestine network was named after an ancient German legend that, if a ghost of a white lady appeared, she would herald the downfall of Imperial Germany.

In choosing this name, the network's leaders believed that its clandestine work would bring an end to the German occupation of Belgium and the downfall of the German royal family. In the end it proved true because Germany was defeated and the Kaiser's reign did not survive the war.

By 1916 the White Lady had become a formal network of the British secret service, MI6, whose head was Mansfield Cumming - the man who first signed his letters 'C' in green ink. This is something the head of the service still does today. Some 1,084 agents served in the White Lady, more than a third of whom were women.

This was an army in the shadows, an army without uniform or guns, whose members took an oath of allegiance and were given military ranks. The men and the women equally swore an oath of allegiance and were given a military rank and, in some cases, the women outranked the men. They used early spycraft in their operations, including invisible ink, knitting simple codes into scarves and hiding messages in items such as potatoes, broom handles and bicycle valves.

Reports were smuggled into unoccupied Holland with information on every train that transported German troops across Belgium, north-eastern France and along the Western frontline. Theirs is a heroic story that is still relatively unknown outside Belgium, but it is one in which the authorised MI6 history later recorded was "the most successful single British human intelligence operation of the First World War". That is some accolade.

When war broke out again, 21 years later, the same leadership was prepared to do it all again. Walthère Dewé received a visit from an MI6 officer who asked him to call up the old guard of La Dame Blanche and start a successor network. This time it was renamed the Clarence Service - named after his co-leader Hector Demarque - and its agents given military ranks.

But its job was the same. The network operated as an early warning system of a German invasion, which did indeed occur in May 1940 when German troops crossed the border and occupied Belgium again. Agents delivered critical eyewitness information for MI6 that enabled Allied commanders to build a picture of German positions behind the lines and provided an extraordinary volume of detailed military intelligence.

Their reports in the nine months prior to D-Day in June 1944 produced volumes of valuable information on things like German troops and their movements, the results of Allied bombing sorties on railway lines, engine sheds and locomotives, enemy activity at aerodromes and sketches of a range of important sites.

Blueprints of stations and rail lines were smuggled out to London. These impressive blue and white technical plans unfurl to a length of two to three metres and survive today in the Imperial War Museum. Women served as heads of intelligence sectors, couriers, agents and ran letterboxes and safehouses. They were as courageous as the men and undertook the same personal risks. Thérèse de Radiguès and the Tandel sisters were examples of this and they became heads of sectors and agent handlers.

Thérèse's agents, many of them women, went on to deliver crucial V-weapon intelligence, including the positions of V-1 installations in France and Belgium as well as the movements of V-1s and V-2s and their component parts across Belgium.

The agents operated beyond Belgium into northern France, where they were particularly active along the coastline and near sites of German defences. Others were sent on clandestine missions from Belgium into Germany and, as the war progressed, they went deeper into Nazi Germany to gather information.

From the London end, operations were headed by 'Major Page', the alias for Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Jempson who headed the Belgian section of MI6.

Working with him was a young MI6 intelligence officer in her twenties, Ruth Clement Stowell, an agent handler who organised the training and planned and oversaw the secret missions of the agents being parachuted into Belgium and the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. They were radio operators who formed the vital clandestine communications between London and Belgium working in enemy-occupied country. Ruth oversaw their missions, often being the last person to see them as they left on their flight from Tempsford airfield in Bedfordshire. She was awarded the Chevalier of the Order of the Oaken Crown by Luxembourg and her pivotal role in this history has been completely hidden for 80 years.

Just a fortnight before D-Day, reports were urgently required on the markings on enemy aircraft, types of aircraft engines in production as well as manufacture of special equipment and weapons, the movement of planes, location of headquarters and state of the railways and traffic in Belgium and northern France. Agents were able to provide this. The vast intelligence-gathering across Belgium, northern France and Grand Duchy of Luxembourg by more than 1,500 Clarence Service agents was simple but incredibly effective.

All this work was as risky then as in the First World War. Some of the network's agents paid the price - shot by German firing squads - or served long prison sentences in horrific conditions of forced labour. Walthère Dewé himself did not survive - shot in the street on 14 January 1944 whilst fleeing the Gestapo.

Today a commemorative plaque in Rue de la Brasserie in Brussels marks the spot where he died. He is one of Belgium's greatest heroes. What emerges from the declassified files in archives in Brussels and London is a story of defiance, valour, ingenuity and leadership that saw Belgian women and men engaged in daring acts of espionage behind the German lines.

The authorised MI6 history says that the Clarence Service was "the highest among the networks of military information of all occupied Europe". The highest praise for a network that most of us have never heard of.

I have only tapped the surface of Belgium's espionage history in two world wars but already there is a sense emerging of the strategic importance of Belgium and one that has been overlooked for far too long.

Belgium may yet emerge as the highest asset to the Allies during two world wars and outweigh other countries that have been the focus of war studies for the last 30 to 40 years.

Surely it is time for Belgium to receive due recognition for its heroic role and the enormous part its agents played in the defeat Nazi Germany and the restoration of democracy in Europe. Their stories remind us of the price paid for the freedoms that we enjoy today.

It was Peggy van Lier, a Belgian agent of the Comet escape Line of the Second World War, who once said: "It is only when you have lost freedom that you realise it is the most precious thing." The women and men of La Dame Blanche and Clarence Service understood this. To them we owe so much. What a legacy!

- The White Lady: The story of two key British Secret Service networks behind the German lines, by Helen Fry (Yale University Press, £20) is out now

You may also like

Roger Federer makes shock inclusion when naming five greatest tennis players ever

Arsenal latest: Zubimendi at centre of 'very bad' row as transfer 'needs' to go through

Gittens decision made as Maresca makes eight changes - Chelsea predicted XI vs Tottenham

Tottenham predicted team vs Chelsea - Romero returns with two big attacking changes

'Captivating' period drama based on literary classic airs on TV today